Don’t Do Small Pull Requests

How asynchronous reviews and wait times harm throughput and code quality

Introduction

In this blog post, I share my learnings in the last couple of months regarding the delivery process of our engineering team at Elli. It was during this time that I came across Dragan Stepanovic’s presentation at the Seattle Software Crafters Meetup. This post is in large part inspired by the work Dragan Stepanovic presented in his talk.

My Hypothesis

During our sprint retrospective, my team and I identified a core bottleneck in our delivery process. During our sprint, we worked on pull requests (PRs) that stayed open for an unusually long time, waiting for reviews, comments to be addressed, merge conflicts to be resolved, you know the deal. As a way to eliminate this bottleneck, I suggested: let’s simply slice our tasks and PRs to smaller parts. My hypothesis was that smaller PRs are easier to comprehend, thereby allowing more thorough and time-efficient reviews and, as a result, increase our team’s velocity and code quality. I was convinced this would be the solution to our bottleneck.

The Method

In order to test my hypothesis I did two things:

- First, I started to slice my PRs to really small parts.

- Second, I decided to analyse some data.

I analysed the following variables over the course of 9 months:

- Size of the PR: the unit of measurement for PR size in this case would be the number of changes that this PR includes. Azure DevOps reports a “change count” metric for pull requests, which we will conveniently use for our data analysis.

- PR’s Time to Completion: The total time (in business hours) taken from the point at which the PR was opened to when it was merged.

- Reaction time (or wait time): The time taken for a reviewer to “react” with a comment or an approval to the PR.

Disclaimer: This analysis does not consider the corresponding tasks and therefore ignores the time spent before the PR was created.

The Analysis

Do we increase our velocity when we slice asynchronous pull requests to smaller parts?

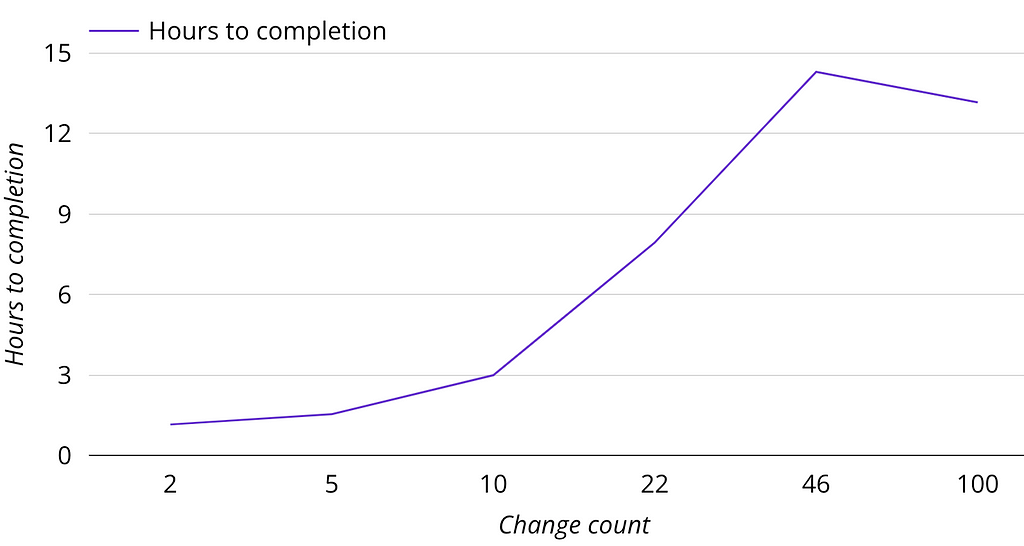

To get a better understanding of the relation between PR size and time to completion, I plotted a line chart that shows the number of business hours spent until the PR merges. The graph clearly shows that smaller PRs complete faster, which we all probably assumed from personal experience. The drop-off to the far right in the graph is an interesting exception and we will get back to this in a later part of this post.

However, when I sliced my PRs really small I did not get the impression that I completed my work faster, rather it felt like the opposite. The next graph reveals that the time per change actually reaches its maximum when change count is really small (to the left) and reaches its minimum when change count gets exceptionally large (to the right).

Ultimately our goal is not to get as many PRs closed as possible but to merge meaningful code. If we want to achieve that in the fastest way possible we should, in fact, make larger PRs, according to these numbers.

Yet, in the middle, there is an interesting minimum on the completion time per change at 5–10 changes, which suggests that slicing a 22 change-PR in half actually reduces its time for completion. Let’s look at this dip more closely, since this area is quite important (we merge 50% of our changes as PRs with a change count between 5 and 23).

What is the effect of asynchronous comments and responses?

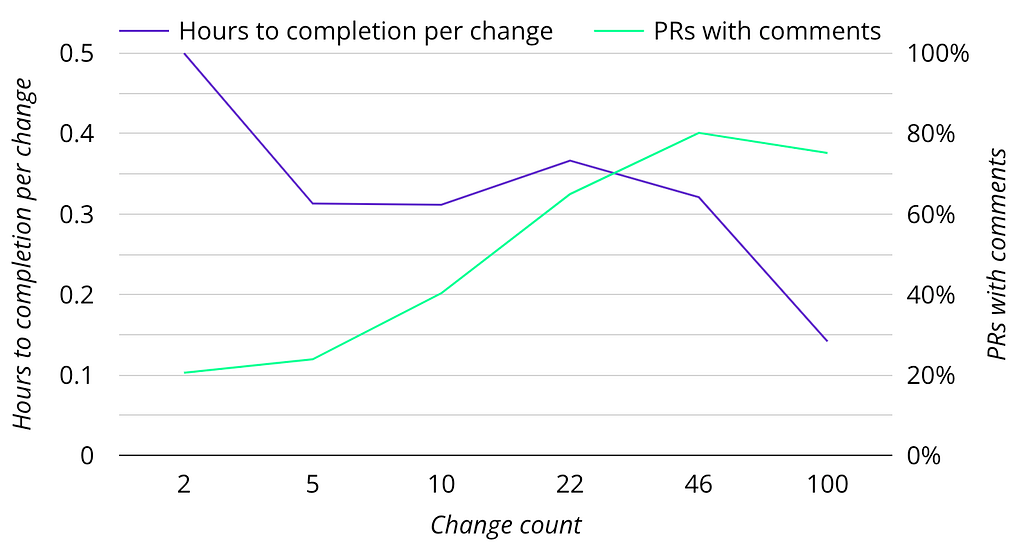

The green line shows the percentage of PRs with one or more comments. Below 13 changes there are more PRs without comments. Above 13 changes there are more PRs with comments. This asynchronous discussion that arises as a result of comment submission leads to the increase in the time to completion. Below 13 changes, the wait time for a reviewer to react to a pull request makes up a large part of the time for a PR to complete. Above 13 changes, the initial reaction time (or the wait time taken for a reviewer to react) makes up less of the total completion time since the asynchronous discussion includes not just the initial wait for comments but also addressing them, and potentially further review loops.

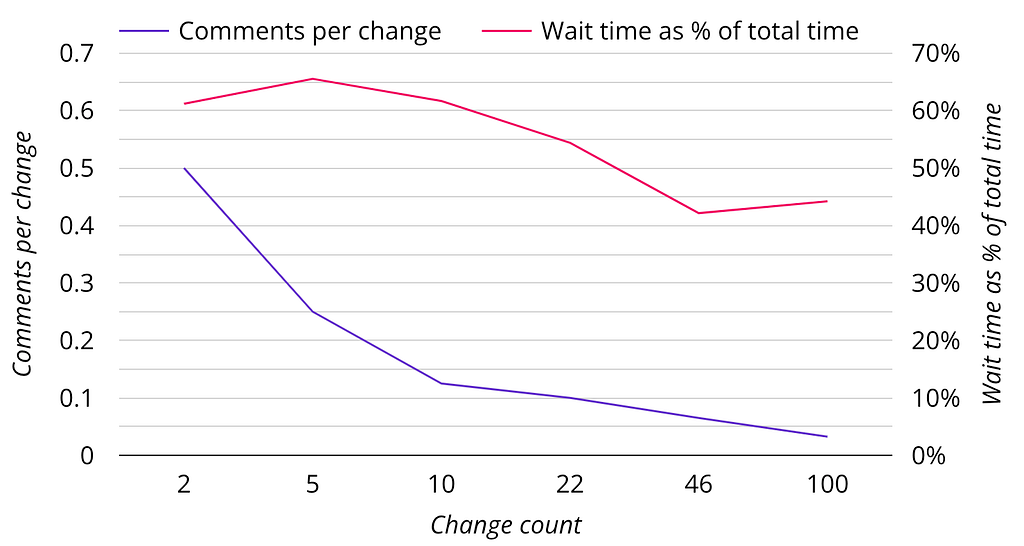

How big is the impact of these reaction times actually? To gauge the size of this impact, I plotted the wait time until the first reaction (approval or comment) as a percentage of the total time taken for the PR to complete.

We see that especially for smaller PRs this initial reaction time makes up the majority of the time to actually complete the PR. Yet, even though the majority of small PRs get approved without any comment from the reviewer, the ratio of comments per change is still the highest in this area. We would conclude from this that we get the most in-depth reviews on these small PRs, but for many, the code can be merged right away. So what do we make out of this now?

My Findings

- To get the best combination of merging changes quickly but still receiving an in-depth review we should aim for medium-sized PRs.

- On these medium-sized PRs, the reaction time makes up a considerable portion of the total time to complete the PR. Therefore, there is quite some potential to speed up delivery by keeping any reaction time low (i.e. complete reviews, addressing comments or pipeline failures as efficiently as possible)

- The first chart showed a drop-off in the “time to completion” for very large PRs. This is due to the fact that many of these PRs have been completed in pairing mode. At Elli, we tend to do large refactoring’s or complex business logic implementations via pair programming. Instead of doing the review process asynchronously, where one person creates the PR and another reviews, we synchronously code and review in the pairing session. Therefore, there are no comments on the PRs and approval may be granted right away. This leads to the drop in the completion time for very large PRs, but this reduction should very well apply to medium-sized PRs as well.

Conclusion

Going back to the initial problem of long-running PRs in our retro, I would now no longer simply recommend slicing the PRs to really small pieces as a blanket solution to faster delivery times. Instead, I would recommend slicing PRs into parts such that the “heavy lifting” is done via pair-programming. The more independently manageable PRs should have a medium size to justify the wait times of asynchronous reviews.

But ultimately, there is no magic number when it comes to pull request size. However, what I did discover from my data analysis were several important guidelines to keep in mind in order to optimise the pull request workflow of our product teams. I hope these findings are useful and extend to anyone who is interested in improving delivery times within their team or organization.

Learn More

At Elli, we are always in search of data-driven ways to improve the way we work together as a team. If you are interested in finding out more about how we work, please subscribe to the Elli Medium blog and visit our company’s website at elli.eco! See you next time!

About the author

Matthias Förth is a Product Owner and former Software Engineer focused on backend development. His current interests are the streamlining of development and pushing data-driven decision making at Elli.

Don’t Do Small Pull Requests was originally published in Elli Engineering on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.